TDTlite

Table of contents

- Set up the project structure

- Add a MACROS file

- Create pattern files

- Search the corpus and build your database

In this tutorial, you’ll set up a simple TDTlite project culminating in a .tsv database of instances of “some” with additional information about each instance – e.g., the match’s unique TGrep2 ID, the full sentence, whether “some” occurs in the partitive, and whether “some” occurs at the start of a sentence. To do this easily, use TDTlite, a wrapper that allows for batch calling of perl scripts that make up the TDT.

Throughout this tutorial, we will be using examples from the alt-right news site “Breitbart”, investigating how they use language to talk about transgender and non-binary individuals.

Set up the project structure

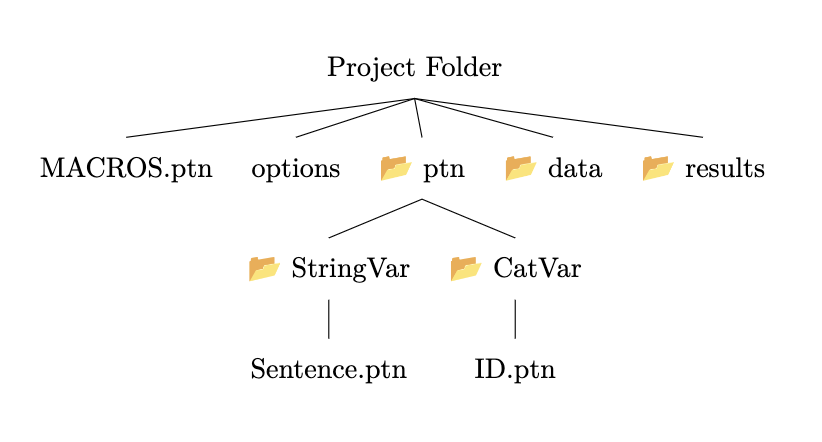

This section provides a project structure skeleton for setting up your project. We’ll go into more detail about what each of these folders and files does in time, but to begin you should have a “project” folder. This will house all the files needed for your project. Inside of this folder, you should have:

1) A “ptn” folder. This folder consists of two subfolders, called “StringVar” and “CatVar”.

2) A “data” folder.

3) A “results” folder. This is where the results of your queries will go.

You can find the structure you will need represented visually below:

Add a MACROS file

Next, we’ll want to create a MACROS.ptn file inside the project folder. This folder will store all the tgrep patterns that we will be able to call in our other pattern files.

A good couple of default patterns include:

@ WORD /^'{0,1}[a-zA-Z]+.*/;

@ TERMINAL * !< *;

@ NP /^NP/;

@ VP /^VP/;

@ PP /^PP/;

@ DISFL /EDITED|UH|PRN|-UNK/;

Note the structure of each macro: on a new line, place an “@”, followed by a single space and the name of the macro in all caps. Then tab once and write out the macro, and end each macro with a semicolon.

We will also want to add the specific patterns that we’re going to make regular use of in our investigation. For example, we might want to be able to find the sentences that contain the bigrams “trans(gender) woman” and “biological male”. We can turn these into macros that we can use later:

@ BIOMAN /biological/ . /\bmale\b|\males\b/;

@ TRANSWOMAN /trans|transgender/ . /woman|women/;

Note that the ‘\b’ delimiter is used here to ensure we don’t erroneously pick out ‘biological female’.

Create pattern files

Now that we have the MACROS file set up, we need to set up pattern files (.ptn extension) that our queries will call. Here, we get to use the MACROS that we initialized in the last step! There are two kinds of patterns we’ll be using in this: Categorical Patterns and String Patterns. We will take each of them in turn here.

Categorical Patterns

Categorical Patterns (or variables) are used to determine if a particular value is true or false, and this property will enable us to define an “ID” pattern that, when matched (=true), will add the occurrence to our output database. Let’s do this now.

First, we navigate into the “CatVar” directory, which is located in your “ptn” folder that we created in the steps above. We’ll create a new file called “ID.ptn”. Inside this, we’re going to define the pattern that we’re looking for in the search. For example, let’s say that in this query we’re interested in looking at occurrences of the bigram “trans(gender) woman/women”. Luckily, we’ve already defined this as a pattern in our MACROS file, so we don’t need to write out the pattern again. Instead, all we have to do is call the macro inside the “ID.ptn” file:

@TRANSWOMAN

And that’s it! Now, when we run a query, a new entry in our database will be created anytime the program encounters the pattern we specified in the “ID.ptn” file.

COMING SOON: Other ways to use CatVar patterns!

String Patterns

If we were to run our search now, it would work, but it would just return a bunch of numbers indicating where in the corpus the matches with the “ID” pattern are. This isn’t particularly useful, since we want to know what sentences the queries occur in. That is, we want the actual text that matched! This is where StringVar or String Patterns come in, as they allow us to add actual strings corresponding to patterns to our output database.

The most basic of these patterns is the “Sentence.ptn” pattern. When implemented, this will allow us to see the whole sentence that our match occurs in. Let’s make it now. We’re going to navigate this time into the “StringVar” directory inside the “ptn” file, then create a new file called “Sentence.ptn”:

@TRANSWOMAN >> (*=print !> *)

This patter basically says: find the highest node (or, literally, the node which is dominated by no nodes) in the sentence identified and print everything within that node (i.e. the whole sentence).

If we were to run the search now, we would get both the matches and the sentences they occur in! For many projects, this might be sufficient: we’ve searched the corpus for a particular construction, and we have a list of all sentences they occur in. However, there may be other string features of the sentence that we want to print in our database for analysis. Let’s take an example.

We now have a list of all the times “Breitbart” uses the phrase “trans(gender) woman/women”. But maybe we want to add an additional variable to our dataset which asks: in each of these occurrences, are the authors saying “trans woman/women” or “transgender woman/women”, maybe because we predict “Breitbart” to use “transgender” more than “trans”. With our setup, it’s easy to add this in! All we have to do is create a new ptn file and specify that we want to print the node where “trans” or “transgender” occurs. So we make a new file called “Trans.ptn”:

/trans|transgender/=print . /woman|women/

Again, this basically just says: find the same pattern as in the “ID.ptn” file, then print the content of the node that contains the modifier. Now, when we run our query, it will print both the sentence AND the exact string value in the modifier position!

Search the corpus and build your database

Almost time to run our search! But first, we need to create one final file: the options file. This file spells out the path to the relevant data and results, as well as the patterns we want to be identified and returned in our final database. All we need to do is create an “options” file in our project directory, specify the paths, and add the patterns we want returned. In this example, the options file will look like:

data=usr/projects/projectFolder/data/

results=usr/projects/projectFolder/results/

init ID

add StringVar Sentence

add StringVar Trans

The “init ID” line says: use the pattern specified in “ID.ptn” to find matches. Then, once matches have been found, run the patterns in the StringVars “Sentence” and “Trans” and add those variable outputs to the database.

Now we are totally ready to run our query! We do this by calling the “run” command, followed by flags that specify the corpus for the query to be run on. In this case, we’ll assume you have a parsed corpus called “breitbart” accessible to you. This looks like:

run -c breitbart -e -o

The results of this query will go into the “results” folder of your project directory. You can navigate into it and open the resulting “breitbart.tab” file, which, will look like:

| Item_ID | Sentence | Trans |

| 18:55 | however, debra messing later realized that in posting an image of solely vaginas she had excluded trans women “who don’t have a vagina.” | trans |

| 29:11 | although many trans women undergo surgery to remove their penis and replace it with an artificially constructed vagina, a large number also keep their genital organs intact | |

| 3119 | he referred to the scandal of lia thomas, a transgender woman swimmer for the university of pennsylvania, saying, “so ridiculous.” | transgender |

… and on and on for every instance that matched! That’s it, we’re done!

The beauty of a system like this is that it’s extremely simple to run the same query on a different corpus; all we have to do is specify a different corpus! Maybe we want to examine how the queer news site PinkNews refers to trans women, to compare it against Breitbart. If we already have a parsed corpus of PinkNews, we can just run the same query with:

run -c pinknews -e -o

And now we have both the data from PinkNews and Breitbart!